★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★

Mythical Creatures in Renaissance Art

Essay

ART 113 - Debin

The prompt for this particular essay was to create a 3-piece museum collection with an interesting theme connecting the pieces, explain the works in detail, and conclude with the reason for the theme/works.

Antonio Del Pollaiuolo, Hercules and Antaeus, ca.1475, Tempera on Panel

Sandro Botticelli, Pallas and The Centaur, ca. 1480-1485, Tempera on Canvas

Piero di Cosimo, Perseus Frees Andromeda, ca. 1510-1515, Tempera Grassa on Wood

Renaissance means rebirth. The rebirth of ideas and culture from classical periods, resulting in content reminiscent of ancient times. Art was no exception to this rebirth. Throughout the Renaissance period, there is an acute interest in the classical works of the Greeks and Romans, particularly regarding mythology. A popular topic for artworks of the time was the stories of heroes and gods, and with that, the defeat of mythical creatures. Many of us know the stories of Medusa or the sirens, the cyclops or the Sphinx. These tales fascinate and inform, and usually the creature at the center of it all can be the most memorable aspect. That is what this exhibition will focus on: Mythical Creatures in Renaissance Art, their prominence in the work and scene, and even the meaning behind their appearances. Additionally, something interesting to note is the, not uncommon, but still relevant connections to the Medici family, a prominent art patron, through influence, commission, and content of the works below.

Hercules and the Hydra (ca. 1475) is the first piece in this exhibition of mythical creatures in Renaissance art. In this work by Antonio del Pollaiuolo, we see a nearly naked man taking up a majority of the frame. He lunges towards a creature with multiple heads, one hand on one of the monster’s necks, one hand brandishing a club above his own head. The creature, which looks like a snake-lizard hybrid, is reared back, its snake-like heads curved away from the man. Its tail is wrapped around the man’s calf and its clawed hand is dug into the back of the man’s knee. The man wears the skin of a lion atop his head, which billows out behind him and wraps around the top part of his thigh. This billowing, along with the forward movement of the man and backward movement of the creature, creates an active piece. We can see the action move laterally, from left to right, across the work, almost like reading a book. It gives the work vitality and weight, rendering it more realistic and substantial. However, while the figure looks more realistic than previous medieval works, there is still a stiffness to the man. This is due in part to Pollaiuolo’s tendency to depict every muscle at the height of tension. In an effort to show off his knowledge of the human body and produce a realistic depiction, Pollaiuolo renders each muscle group as 100% engaged, resulting in a man almost frozen, as if he is holding his breath. The painting as a whole, however, still feels in motion, with the position of both the man and the creature implying movement and intent in the scene. The scene itself takes place atop a hill, the landscape receding into the background, utilizing atmospheric perspective as the color and clarity of the sky and ground lighten and fade to produce depth and space in the work.

The iconography of this piece is classical in nature, depicting the Greek hero Hercules slaying the hydra, a mythical beast that, upon losing one head, can grow two more in its place. This scene represents one of the Labors of Hercules, a series of trials the hero had to complete in order to be absolved of the murder of his family, a crime he committed under the influence of the goddess Hera. In addition, the lion skin Hercules wears is that of the Nemean Lion, another mythical creature with impenetrable skin that the hero was tasked with killing in a previous trial. This piece is on par with the revitalization of classical themes in art that took place during the Renaissance. Families like the Medici, who were the first patrons of this work, although the original commissions were lost and had to be redone for a different family, were particularly fascinated with Greco-Roman mythologies, and that, along with not one, but two mythical creatures make Hercules and the Hydra an excellent addition to this exhibit.

The next piece in this exhibit is Pallas and the Centaur (ca. 1482), by Sandro Botticelli. In this work, we see a woman adorned with leaves, long flowing hair, and a thin, transparent garment, gripping the hair of a half-man, half-beast. The creature has the head and torso of a man with the body of a horse. The woman holds an axe and appears unaffected by the creature, standing proud and full of power, while the horse-man hybrid is clearly in distress at being physically dragged by the hair, appearing weak and at the mercy of the woman. There is a slight atmospheric perspective to the piece, as we can see a lake and hills in the background, but the majority of the work is relatively flat. In contrast to Hercules and the Hydra, this work appears to be all on the same level does not look as if it is reaching as far into the background as the first work. Additionally, while they are realistic, the anatomy and musculature of the two figures are clearly not the focus. Rather, like other works by Botticelli, we are meant to fixate on the symbology and poetic nature of the characters in the work.

The actual iconography of Pallas and the Centaur is up for interpretation. This work does not depict a particular scene, and the identity of the woman is somewhat ambiguous. She could either be Pallas Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom and battle strategy, or she could be Camilla, a virgin warrior, who died in battle defending her country. The leaves covering the woman could be either olive (sacred to Pallas Athena) or myrtle (associated with Camilla). The beast is what is known as a centaur, half-man, half-horse. He is meant to symbolize the feral instinct of humanity. By contrasting either Pallas Athena, a virgin goddess, or Camilla, a virgin warrior, with the centaur, the meaning of the work becomes evident. The woman, a symbol of virtue, grips and restrains the centaur, symbolic of savage temperament, becoming an allegory of virtuous life curtailing the wild nature of humanity. Use of allegory is not uncommon in Botticelli’s works. He often used these fantastical stories in the same way that poems or pageants of the century used allusions to myth to display something introspective, chivalrous, or romantic. Additionally, this visual poetry parallels the poetic work of Lorenzo de’ Medici, a member of the family that commissioned this particular artwork, giving the work another layer of meaning in the context of the family, whose insignia is the three-ringed decoration on the woman’s garment. It is a nod to the patrons, as well as a beautiful depiction of poetry and symbolism.

Piero di Cosimo’s Perseus Frees Andromeda (ca. 1510-1515) is the final work in this exhibit, and perhaps the most complex of the three in terms of scene and story. In the center, we see a man standing atop a sea creature, brandishing a sword. The man has winged shoes on his feet and is twisted around as if in preparation to swing at the beast. The sea monster, with its long tail and tusks, is the largest figure in the piece and draws the focus of the viewer. The creature is snarling at a woman tied to a tree, drawing back in fear. In the upper right-hand corner, we see what appears to be the same man, flying in with winged shoes. In the lower left-hand corner, there is a group of people, all brightly colored, in various states of distress, as they watch and cower from the beast and the scene of the tied-up woman. In the lower right-hand corner, there is another group of people, with what appears to be both the man and the woman in the center, celebrating, playing music, and waving leaves in the air. Their facial expressions are much happier than those on the opposing side. There is much detail in the piece, from the scales of the creature to the rippling water to the intricacies in the garments. The work includes both atmospheric and linear perspective, with orthogonal lines reaching back diagonally to the horizon line, losing color and detail as the scene reaches farther back. In addition, the cliffs and buildings on either side of the background frame the work, curving in the focus. There is also a diamond-like shape to the composition, the water coming to a point in the foreground, shortening the width and depth of the ocean, and reaching backward at an angle, deepening and stretching the landscape. This shape makes the water where the sea creature is sitting seem like a pond, but still makes the scope of the painting as a whole appear massive.

The story depicted in this work is that of Perseus and Andromeda. In this story, Andromeda’s mother, Cassiopea, Queen of Ethiopia, offended the Greek god Poseidon. In retribution, Poseidon sent a sea monster to terrorize the city, only to be appeased with human sacrifices, in this case, the princess Andromeda. Perseus, on his way back from slaying Medusa, happens upon the scene and saves Andromeda’s life by killing the sea creature. What is interesting about this painting is that Cosimo depicts the whole story, from beginning to happily ever after, in one scene. Rather than just showing the entrance, the fight, or the celebration, he depicts Perseus in all three stages of the story: flying in with his winged shoes (upper right-hand corner), fighting with the sea creature (center stage), and celebrating with the newly freed Andromeda (lower right-hand corner). The intent of the artist is to make the whole story as clean and understandable as possible, in one piece of art rather than three. It is not so much about the drama or the action of the myth. Cosimo simply wishes to inform the viewer of all aspects of the tale. It should come as no surprise that this work is also tied to the Medici family. This work was most likely commissioned as part of a nuptial room, specifically that of Filippo Strozzi the younger, and Clarice de’ Medici. The connection to the Medicis, as well as the addition of the mythical creature, relate this piece to the other two discussed and round out the exhibition.

Although these three works are joined through Medici and monster, there is still more that relates them to one another. Looking at each of these pieces, there is a great sense of power that washes over the audience. Whether that power is displayed in the action and structure of the figures themselves, as with Hercules and the Hydra, in the allegory, as with Pallas and the Centaur, or in the telling of the story itself, as with Perseus Frees Andromeda, the gravity of the work is apparent upon observation. That deep feeling of authority, whether that feeling is directly seen or indirectly shown, winds through these paintings and tumbles out to the viewer, connecting them in a way beyond family and creature.

Monsters are visual representations of fear, hatred, and sin. The heroes that slay them are the opposite; the best parts of humanity. By pitting the two against one another, the classical and Renaissance thinkers alike, represent the power struggle between what is right and wrong. At the core of everything, philosophy, mythology, religion, etc, is the battle between good and bad. And while we may be able to read and write about these ideas, there is something about art that shoves it in our face. We can see, feel, and experience that emotion and that struggle as clear as day. We can relate to the heroes, as well as the monsters, in a way that pulls our own morals and vices up to the surface. We want the hero to win, and yet we may still feel the pain of the creature in its submission or defeat as if it is our own. Art does this like no other medium, expressing the power of story, of action, and of symbolism so transparently, we cannot help but see ourselves reflected back, regardless of the fantasy.

★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★

Seeing Red: The Use of the Color Red in Mayan Art

Essay

ART 116- Debin

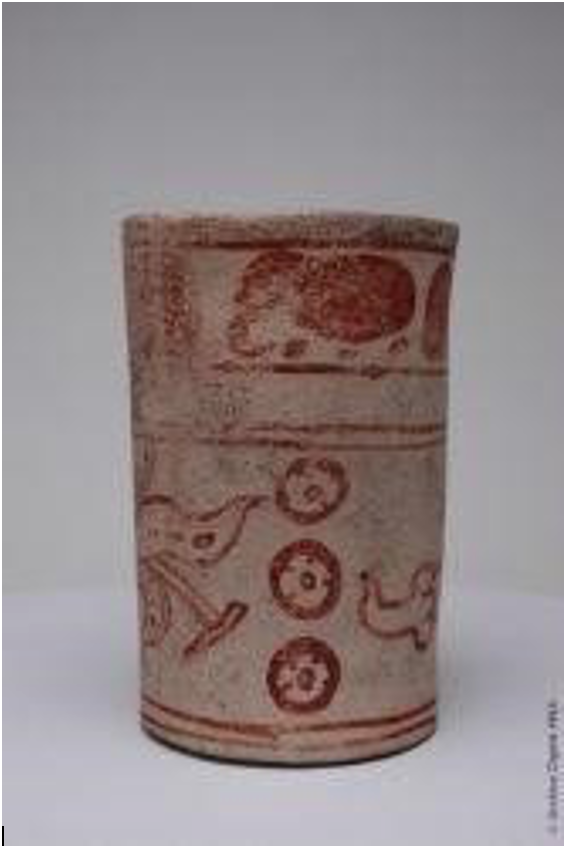

Vaso, ca. 250-950 CE, unknown material, 17.80 x 11.60 cm

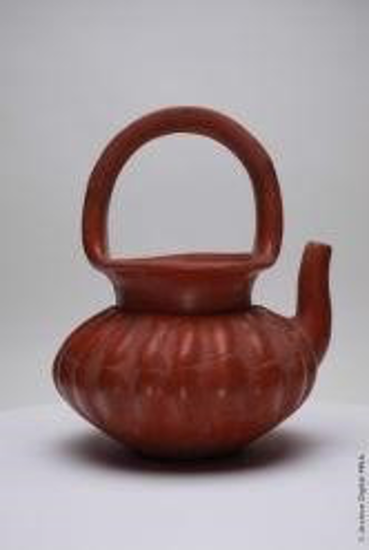

Olla, ca. 250-950 CE, unknown material, 26.80 cm x 22.10 cm

Plato, ca. 250-950 CE, unknown material, 5.20 cm x 33.80 cm

Mayan art is full of color. Although centuries have passed and artifacts have been buried in dirt, the bright colors of Mayan art still shine through. The pigments and natural coloring the Mayan people used have a longevity that has survived to this day. One color, however, seems to have persisted longer than most: the color red. Palaces, tombs, pottery, and everyday objects were painted red, and the fact that many of these red objects are still around today is a testament not only to how durable the achiote-based pigment was, but how essential the color was to the Mayans. Red, or chalk, was known as the cardinal color of the East in Mayan culture. It was a symbol of the sunrise, a new day, and a new outlook on life. The color plays into maturity, knowledge, authority, and leadership. It even plays into a Mayan creation myth involving bloodletting and cacao beans. Whether it is used as an accent or as a statement, the Mayan people incorporated this bold color into many of their works, making the color essential viewing for anyone studying Mayan art. The three objects described below are a testament to how color and meaning seeped into everyday objects like plates, cups, and cooking pots. In this collection, we are going to focus on three objects that utilize red in specific ways, in reference to symbology, mythology, or just plain design quality.

The first item in our collection is what appears to be a cylindrical container (250-950 CE). The object is 17.80 cm in height and 11.60 cm in diameter. It is a light-colored object with red details and images. The container has straight red lines around the circumference of it, cutting the object into different layers of design as the eye goes down. The first level at the top has wavy, free-form designs painted around the container. These forms are filled in with red, although time has made some of them difficult to depict. The next layer is empty between the lines, and this space is bracketed by a single line at the top and a double line at the bottom. The next and final layer is the largest and has the most designs inside the level. These designs appear to be outlines rather than filled-in forms like the ones above. These forms consist of mostly rounded lines as well, although, once again it is difficult to discern what the forms are might be. The most visible design element in this layer are three circles, one on top of the other, with a dot in the middle of each one. These circles are done in freehand, as each form is slightly different from the other. The end of the layer and the bottom of the container is punctuated again by double lines. The rounded nature of the designs coupled with the straight lines dividing the container creates a great juxtaposition within the piece, contrasting the straight lines with a curved design and producing an interesting piece to look at. The reddish-brown pigment pops against the lighter-colored container, making the design elements clear and eye-catching. Containers like this were very common in Mayan life, although most of the more well-known pieces are more highly decorated. This piece was probably an everyday cup and could have possibly been made to house a popular chocolate beverage, as was the case with many vessels at the time. This container has similar elements to the walls of the tomb in Río Azul, in Northeast Guatemala. The color, as well as the use of said color on a lighter background, is reminiscent of the tomb. The strong and calligraphic lines, and the confidence in which the piece is painted draw a comparison between the two works. Although the designs may not be exactly the same, the similarities present may help to place the container as an Early Classic piece of Mayan art. The striking use of red as a way to make the details stand out additionally places this piece firmly in our collection.

The second piece in our collection is a Mayan ceramic cooking pot (250-950 CE). The piece is 26.80 cm in height and 22.10 cm in diameter. The pot is entirely red and brings to mind a modern-day teapot or kettle. The cooking pot has a rounded body, with a curved neck like a spout. The widest part of the pot is in the center of the body, with the base as the narrowest section. The top of the body leads into a circular opening and wide lip. The handle of the pot is similar to a basket’s and the body of the pot is designed with a measured pattern, almost like a squash or plant. The pattern is symmetrical throughout the pot and creates an aesthetically pleasing, albeit simple design. This piece was probably used in everyday cooking. Due to the color red being associated with the sunrise, it is possible that this pot was used in the morning, explaining why it would be colored in this way. Additionally, red is also symbolic of ripeness in corn, fruit, and other crops, relating the specific use of the pot for cooking, to the color red. By coloring this cooking pot red, the Mayans were acknowledging their beliefs and the importance of the color red in their culture and in their everyday life. The importance of red as a symbolic detail in this cooking pot makes it an excellent addition to this collection.

But what is the point of displaying such ordinary objects, when there are plenty of extraordinary pieces in Mayan art? These pieces and this collection were chosen because of exactly that: they are ordinary, everyday objects. Sometimes a viewer can get so caught up in the grandiose nature of temples and paintings, that simple, commonplace artifacts can slip through the cracks. The artistry and importance of something as ordinary as a cup, a pot, or a plate is overlooked, when it should not be. The purpose of this collection and these particular pieces is to show how things like meaning and religion, care and attention, and most importantly artistry, can permeate even the simplest and most common of objects, and make them into something worthy of being displayed for all to see.

By looking at everyday objects, we get to see the way, ordinary people like us lived, ate, cooked, and much more. Furthermore, we can see what was important to everyday people and families and what they cared to depict, design, and simply possess. Additionally, we can see just how far-reaching the beliefs of the Mayan people went and how important color and symbology were to them. Red is the color of the new day, the color of knowledge and ripe crops, and the color of leadership. By looking at these everyday objects, it is clear that these ideas were extremely important to the Mayan people. Red has permeated many aspects of Mayan art, and the fact that so many of the objects around today are colored red shows us just how much the Mayan people respected and craved objects of that color. Everyday pieces like the container, cooking pot, and plate above reveal the importance and influence of a simple color on an array of art and how through art, the Mayan people revealed their culture and their beliefs in everyday life.