Lovesick

Acrylic

ART 189 - Cummings-Sumner

This was a Pop Art class assignment inspired by Roy Lichtenstein comics of the 1960s merging with the issue of the pandemic we are experiencing in modern times.

★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★

Symbolic Self-Portrait assignment. Concept of time in various forms, memories under lighting clouds in the tendrils of hair. Mountains and sand dunes of an ardours journey in the distance. 3 suns respecting the passage of days as well as 3 lives. Green grass hills exhibit red memorial poppies, plumeria's for new beginnings, and California Golden poppy for golden times to come. Rainbow on the back of the female figures mind/head, to indite the attempt to still have hope for a better future. The female figure meditates on life in a transitory state attempting to be still and gain peace.

See this artwork in the Portraits Exhibition.

★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★

The Evolution of Women in Art

Essay

ART 112 - Debin

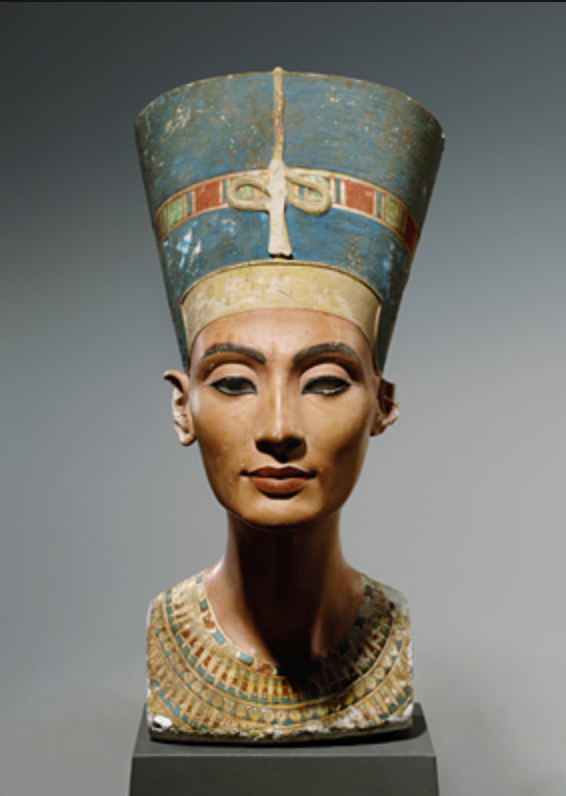

Art History 112 Ancient to Medieval final essay, The Evolution of Women in Art: Conceptual to Quintessential. In this essay prompt, the goal was to choose 3 pieces of artwork for our own fictional exhibit with a theme and title that connected them. I chose The Venus of Willendorf, The Bust of Nefertiti, and The Marble head of an elderly woman. My goal was to connect the evolution of women in art to the evolution of the perception of women as human beings, firstly as functional, secondly as a deified aesthetic, and lastly as real individuals who share life experiences.

The Venus of Willendorf

The Bust of Nefertiti

The Marble head of an elderly woman

Art was the earliest form of communication for humankind from cave art such as wall paintings and painted handprints to carved statues that developed further into sophisticated language. It was arguably the first evidence of the philosophical statement, I think therefore I am or rather I see therefore I create...what I comprehend. From our earliest findings of art of other humans, women are the dominant subjects rather than men. In art history women continue to be a major focal point in artistic expressions often produced by men.

However their representations, though glorified, also express a limited understanding of the female as human beings of equal reality, capability, and value as men. That is not to undermine the value of the developmental progress of each art piece in technological advances being necessary steps towards reaching a fuller understanding of many aspects of human life. Women were important enough to the artist or society to attempt to produce their likeness according to the artistic and technological standards of their respective times. The intention of our exhibit, The Evolution of Women in Art: Conceptual to

Quintessential, is to isolate that focal point of art’s developmental communication of its comprehension of women throughout history.

Our first art piece is Nude woman known as the Venus of Willendorf from Willendorf, Austria, created in about 28,000–25,000 BCE of the Paleolithic period. She is made of Limestone and about 4’ ¼” high. The Venus is all circles and ovals in shape carved in congruence with the natural formation of the stone as well as to capture the distinct body parts of a female. As is common with the female sculptures of this time period the figure is nude, her breasts are overly large with disproportionately small arms resting on them. Her triangular vagina is carved below her round and wide stomach, her vagina has a line for a slit of the vulva. Her thighs are thick with knobby knees turned inward, while lines for every intersection of the body parts express the creases of fatty areas. Her ball-like head is turned downward with no indication of a neck; her faceless head bears either rolls of hair or a woven hat. The hair or hat expands from her hairline to her shoulder line above her wide backside.

Our second artwork is the famous Bust of Nefertiti made by Thutmose in the 18th Dynasty created around 1353–1335 BCE from Amarna, Egypt. It stands 1’ 8” high and is made of painted limestone. Found in a sculptor’s workshop in Amarna, Thutmose is attributed to the creation of this bust whose namesake was a queen of Egypt. She dons a large heavy looking blue crown of Egypt with a decorative band of green, blue, yellow, and red rectangular pattern similar to her necklace. Her crown’s band bears the emblem of golden serpent as the headpiece. Its shape is that of a cylinder that fans out on the top while retaining its solidness. Her features are of the ideal height of beauty, high cheekbones, straight slim and smooth nose, full lips, and deep set eyes. Her skin is painted brown with brick red lips, painted on dark thick eyebrows, Egyptian style eyeliner, and one of her irises is painted in the white eyelet while the other is not. Her neck is slender, curved and long, possibly exaggerated for the contrast with the heaviness of the crown.

Our third work of art is the Marble Head of an Elderly Woman crafted from about 40-20 BCE in the Roman culture style and workmanship. It was made during the Late Republic or Early Augustan, stone sculpture of marble stands 10 1/4 x 6 1/2 x 7 3/4 in dimensions. This piece was a portrait of a mature Roman woman, a matron of dignity and social status. Her hair is worn high in a braided bun in the back of her head with what is called a nodus, a frontal folded braid pulled back. The paint that used to be on this piece leaves little evidence but some traces of color on the right eye, eyelid, and hair. It is now the natural white and off white tone of the stone. Age and unknown incidences have rubbed off certain features such as the end of the nose, part of a lip, some of the cheeks, and the bun part of her hair was fractured off but is now being held in place. Her features exhibit her natural elderly state, with laugh lines, sunken eyelids that grant her tired looking eyes, small lips, and the sunken area below cheekbones. The Venus of Willendorf iconography is of conceptual woman, the chiseled sculpture of the female body exaggerated her body parts to emphasize the functionality of woman. The detailed lines of the Venus’s breast and vagina made by a sharp burin were produce by incisions into the limestone express women’s capability for reproduction. Red ocher was applied to the body for coloration that has now since faded although such a color would be a strong attraction for a viewer to the figure though it is not believed that this is an image of an actual person but the idea of fertility that females imbue as it lacks a face for individuality. The Venus of Willendorf and her many other sisters of faceless female sculptures with exaggerated female body parts offers evidence that during the Paleolithic period, the valuable, although a one dimensional, view of women was their functionality to reproduce and continue the human species.

The Bust of Nefertiti is made of long lasting limestone and colorfully painted for the intent of honoring the patron, Nefertiti Queen of Egypt. Egyptian sculpture was meant to present the ideal beauty standard of its time, to the point of deifying its leaders rather than the reality. The heavy crown that appears to seamlessly connect to her dignified head on top of an elegantly long and thin neck offers a serpent-like balance of curvature and line. Her chiseled facial structure and symmetrical features along with a swan-like neck are aesthetically pleasing. For Amarna, Egypt, the goal was to capture the spiritual beauty standard rather than the true likeness of the royal subject. Here, ancient Egypt granted Nefertiti the honor of being identified and individualized. Although it was part of the culture for both men and women to be immortalized in ideal appearance, The Bust of Nefertiti expresses the value and comprehension of women is the spiritualization of her aesthetically appealing appearance and to be recognized in relation to her role and connections rather than for simply herself.

The Marble head of an elderly woman from Roman culture held the intention to be commissioned either by the woman or her family. Her likeness was to be captured in her natural appearance as her family would know her and as she would know herself. Her hairstyle communicates her time period due to the time for when it was trending in her society. The smooth stone is chiseled to show flowing lines that indicate the texture and directions of her parted hair and its formation into braids, and bun. The indentation of her forehead, notable brow ridge, wide set eyes, slim nose and small laugh lined mouth are all features that honor the subject’s individuality and the reality of her life experience. Roman culture of her time period valued ancestor portraits and as Republican Rome ruled over diverse amount of people groups, developed more liberal government than the monarchies of the past, people, from aristocracy to middle or lower class citizens and former slaves all could begin to start commissioning representations of themselves in art and sculpture. The shows evidence that both broadly and for women, individuality and actualization of the self could be represented in art, women at least in art could be shown to have equal complexity and accepted as they were rather than conceptually.

The Venus of Willendorf was featured for her being one of the earliest female representations made by human beings. It exemplifies the earliest conceptualization of females objectified as functional for fertility. It exposed a rudimentary understanding of the female side of the Homo sapiens species and the expressed value of women at that time. The faceless Venus artwork is like that of an allegory of fertility, expressing females to be identified purely by the emphasized and exaggerated mechanics of her reproductive parts presenting a one dimensional view. This artwork from the Paleolithic period illustrates comprehension of women in art in an infancy stage.

Jumping ahead to the time of Egyptian Queen Nefertiti, whose very name means, "The beautiful woman has come" we revisit the female concept in art. Famous for its idealized beauty, the Bust of Nefertiti was selected as an example of two-dimensional objectification of women in art. We move from value for functionality in Venus to value on women’s ability to be aesthetically pleasing. Although it was a cultural standard at the time, focusing on idealized features and gaining notice for high governmental status in this instance caused such women at this time not to be depicted accurately but rather the goal was to provide spiritualized representation. This version of Nefertiti is presented as a faultless goddess meant to be admired not known, glorified in the power of her beauty which relates to sex appeal being both desirable and unreachable. This artwork from Egypt’s 18th dynasty period illustrates comprehension of women in art in an adolescent stage.

The Roman portrait, Marble head of an elderly woman, was chosen to provide the bookend of the exhibit, as she exemplifies the final piece of the puzzle of women’s evolution in art. No longer to be objectified by her functionality to reproduce or to be worshiped as a faultless goddess of manufactured youth but to be valued for her own self. Roman artwork had progressively developed toward humanism to value being naturalistic in its imagery to the benefit of many aspects of life, including the conceptualization of women in art. This marble portrait does not hide wrinkles or signs of age, it doesn’t have the rest of her body to show her female parts, and yet we can recognize she is a woman and consider her most likely to have been a real person who actually lived. She is relatable, humanized, reachable, and a recognizable individual. The actualization of women is in expressing her humanity, a reality worth preserving; this shows that women can simply be valued for themselves. This artwork from Roman culture illustrates the comprehension of women in art has finally reached maturity, a stage of adulthood. Collectively we see three parts of the evolution of women in art from conceptual to their quintessential representation. The Venus of Willendorf expressed women’s functionality in fertility, the Bust of Nefertiti illustrated women’s spiritualized beauty, and the Roman portrait, Marble head of an elderly woman, provided actualization of women’s equality in humanity. These pieces are the evidence of the developmental process that help us understand the past comprehension of women throughout these points in history. We can now recognize the three dimensional reality painted by the triunity of these pieces that women possess all these valued features to be celebrated in view of a full picture of the complexity of female representations in art.

This exhibit's intention is to encourage the audience to consider how art history has represented women. From conceptualization to actualization, we would like to offer the observer the tool of adding the evaluating element on whether or not the art they observe is offering a three dimensional view on women and ponder its perceived value to the period’s civilization. Additionally we want to inspire introspection on the complex question of how these respective views advanced or limited the developmental comprehension of women’s equality and value in society. The exhibit, The Evolution of Women in Art: Conceptual to Quintessential, hopes to have offered a fair view of respecting the ages and stages development taking arguably necessary steps to the enlightenment of women’s quintessential value for their shared humanity.

★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★

Art 113 Renaissance to Modern final essay entitled "Self-Expressions", I compare and contrast 3 female painters as I analyze their respective self-portraits. The 3 artists are Judith Leyster, Artemisia Gentileschi, and Elizabeth Louise Vigee Le Brun.

Self-Portrait, Judith Leyster, European baroque artist

La Pittura, Artemisia Gentileshci

Self-Portrait, Elizabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Rococo artist

Art is a method through which we humans have found as a means to express ourselves and how we see the world. Self-portraits express how we view ourselves from an inside out perspective and how we see ourselves interpersonally in relation to our family, social roles, community, region, or experience with our society. Women have had many ways of seeing themselves in relation to the impact of society’s view towards them in history having been given limitations that do not reflect the truth of who they are and what they are capable of. Many examples would take on more of a political connotation such as the woman’s suffrage for their right to vote in a democratic society.

In the same vein, in the realm of the arts, the struggle for acknowledgement has bled over where we find women voicing the desire of equality in the male dominated field. The women painters, who managed to be heard, acknowledged, seen, and valued in their times despite the challenges of gender bias calls for us to rejoice at their success and pay heed to what their work has to say about them. While not patronizing them for being female but allowing them to join the developmental conversation of art in its respective standards of their times and to be evaluated for their own skillful merits. To this end we present our exhibit, Self-Expressions, where we spotlight three female painters and their self-portraits

The first artwork our exhibit features is called Self-Portrait painted with oils on canvas by Judith Leyster in 1630. Leyster chose to stage herself before her canvas while being seated in a chair with paint brushes and palette in hand. In composition Leyster is turned away from the canvas to face the viewer. Her body leans back like a curtain pulled to the side granting us view of her painted creation. Leyster’s back is not supported by the backrest rather her right arm nests on it for support; this position communicates a relaxed confidence. A paintbrush held aloft perches in her right hand as if it had been working and now has paused to greet us. As though a thin stem, her left arm rests at her side while out of her left hand’s firm grasp blooms a palette with a bouquet of paintbrushes and a cloth. The shadow falls from her right arm onto her midsection, defines the crumples in her skirt while gradually darkening the

plain background.

plain background.

Initial attention is drawn to the lighting of her face from the off-canvas light source, the light guides our eyes to her right then left hand and back up to the light on the face of her painting. Her in-progress painting of a jolly fiddler emulates the gradual darkening of her background of her ownenvironment. Leyster’s face appears to be in an open smile, a sense of humor that her jolly fiddler seems to share. The expression communicates a relaxed confidence with a playful smirk as she unveils her skills in both her self-portrait and the painting of the fiddler. Rather than don an artist's smock, Leyster is proudly proclaiming her family status in wearing the wealthy clothing of her time and region. She is shown wearing a lacey white bonnet with a ruff around her neck, a black corset, rose pink skirts with short silk sleeves.

Our second piece is called La Pittura painted with oils on canvas by Artemisia Gentileschi in1638–1639. The artwork is both a self-portrait and an allegory painting where the artist herself is the personification of the art of painting. The Gentileschi has staged herself standing before her easel with palette and brushes in hand. Her body is at an angle turned away from the viewer towards the canvas.

Gentileschi composition is dynamic gained with the use of mirrors. We view her face and figure from the left profile view, angled away from the viewer to such a degree we see the top of her head. Her right hand holds a paint brush about to engage with her blank canvas while her left hand rests on a wooden platform on a table. Her left hand holds a square palette with only three paint brush ends branching out their heads hidden in her grasp.

Her foreshortened face, right forearm, bosom, and the material on her dresses sleeve catch the unseen light source. This lends to the shadow of her palette against her left hand and table, in the folds of her garb, and on the back of her body. Gentileschi is seen wearing her dark hair in a loose bun, her face clear shows a ruddiness in her cheeks, lips, and eyelids. Her richly colored and crinkled sleeves of green burst out of her brown painters smock as a golden linked chain with the pendent of a mask hangs off her neck. The expression of her face appears both serene and focused as her gaze is oddly fixated neither towards us nor the canvas but off in the distance, most likely towards her mirrors of reference. The painting offers the sentiment of a woman engaged in her work.

The third piece of our exhibit is also called Self-Portrait painted with oil on canvas by Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun in1790. Vigée Le Brun has staged herself seated in front of a canvas on an easel with brushes and palette in hand while facing the viewer. Vigée Le Brun’s composition has her right-hand holding a paintbrush against her in-progress painting of Marie Antoinette on blue tinted canvas. A bushel of brushes are held in her left hand along with a palette in her arm’s embrace. The light reflects off the wood of the chair and her palette. Her face is turned towards us and the light source, the lighting then leads us to her right hand and falls to the left hand below her palette. Shadows are cast against the canvas and under the palette. The shadowed background is diffused by the halo of light around her face. From her face to her hands we are then guided to the red bow of her gown. The large red bow wrapped around her waist doesn’t compete with the focal points of her luminous skin, a credit to her use of value.

Her long sleeved dress offers a thick appearance with the weighty bow contrasting with the crisp light lace trimmings. The dark elegant material of her dress catches highlights of light to expose its navy blue color. The delicate yellow lace that sprouts out of the neckline and wrists matches her chiffon head

wrap in color. The head wrap exposes her thin delicate curls of hair, light brown in color, that crown her youthful face. Vigée Le Brun’s bright hazel eyes softly meet your own above her pouty pink mouth that offers a small inviting smile.

wrap in color. The head wrap exposes her thin delicate curls of hair, light brown in color, that crown her youthful face. Vigée Le Brun’s bright hazel eyes softly meet your own above her pouty pink mouth that offers a small inviting smile.

The three self-portraits of the painters in the process of painting share overlapping iconography. All three depict the images of painter’s tools of the trade, namely the easel on which there is a canvas, paint brushes, and palettes. After these are established Judith Leyster and Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun share similarities, in postures both are seated and turned towards the viewer. Both have their works of art on their canvases expressing something about themselves. Both are dressed in elegant clothing expressing their status in society missing the traditional and practical painter’s smocks. Standing alone figuratively and in her painting is Artemisia Gentileschi who is not depicting the truest form of a self-portrait but an Allegory of Painting. She stands turned away from the viewer in a dynamic angle that shows a foreshortened profile and the top of her head, there is no image on her canvas, and she is wearing her

painter’s smock over her dress.

painter’s smock over her dress.

Leyster’s canvas shows a comic image which is her iconic signature of favored subjects; Vigée Le Brun canvas depicts her famous patron Queen Marie Antoinette, while Gentileschi wears a golden chain necklace with a mask pendant as she is the embodiment of painting itself. For each the iconography expresses their measure of success as women in the painter’s profession. For Leyster it’s the confidence of inviting the viewer to view both her self-portrait along with her iconic signature, as a painting within a painting. Her self-expression is that she had found freedom to do what she loved or was a least developedskilled at and the freedom to do the subjects she enjoyed. For Vigée Le Brun there is a humble confidence in her graciousness to her patron, success appears to be found in who you know as a means to be elevated to show your skills to the world. Gentileschi looks neither for an iconic signature nor connections nor in status of dress nor even to the viewer, for her success is in the dynamic of doing. She is the embodiment of painting and fully enthralled in becoming one with her art form, she is her own motivation for self-expression.

Leyster and Gentileschi self-portraits illustrate abstraction balanced with humanism. In areas throughout their painting their figures take on realism in more rendered are of three dimensional forms or in other areas flatten with fine lines on the edges of their shapes. Leyster’s palette of color choice is of

middle values with cooler color usage that produce a claiming effect. Gentileschi’s palette is higher in contrast of values with warmer colors along with her figures angle a sense of heated movement is implied. Vigée Le Brun’s self-portrait produces a naturalistic realism in form as well as pose with some idealism in youthfulness of the face and the angelic halo of light framing her head. Her palette is balanced with warm and cool colors that are harmonized in her usage of contrast in values.

middle values with cooler color usage that produce a claiming effect. Gentileschi’s palette is higher in contrast of values with warmer colors along with her figures angle a sense of heated movement is implied. Vigée Le Brun’s self-portrait produces a naturalistic realism in form as well as pose with some idealism in youthfulness of the face and the angelic halo of light framing her head. Her palette is balanced with warm and cool colors that are harmonized in her usage of contrast in values.

Both Leyster and Gentileschi were famous female painters of 17th-century Europe. Their art style was from the Baroque period with Leyster being influenced by artist Frans Hals while Gentileschi was influenced by artist Caravaggio. Leyster’s genres were of still lives, floral pieces, and comic images. Gentileschi subject matter was broad from myths, historical and biblical scenes, portraiture and allegorical paintings. Gentileschi used tenebrism depicting high contrast and dramatically dark imagery in her scenes. Vigée Le Brun was an 18th-century French artist from the Rococo period and excelled in the genre of portraiture along with allegory.

The Dutch Republic, Haarlem was home for Leyster who lived from 1609–1660, although no confirmed teacher is known we do know she studied her contemporary Frans Hals’ work enough to have her work indistinguishable from his after her death. Leyster did well for herself in the profession although

there are no mentioned of high profile clients she was able to gain membership at Haarlem Guild of St. Luke. When Leyster married another painter, they moved to Amsterdam for work, the controversies for her happened after Leyster had died her work became mistaken for Frans Hals. It was till later that her

work was discovered as hers and accreditation was restoring to her name.

there are no mentioned of high profile clients she was able to gain membership at Haarlem Guild of St. Luke. When Leyster married another painter, they moved to Amsterdam for work, the controversies for her happened after Leyster had died her work became mistaken for Frans Hals. It was till later that her

work was discovered as hers and accreditation was restoring to her name.

Italy was the stomping ground for Gentileschi who lived from 1593–1653; her talented father Orazio who was a painter taught her the trade. Gentileschi became a member of the Academy of Florence and had high profile clients, one of which was King Charles I. She married a painter and moved throughout Italy as well as to England during her career; she experienced controversies that she wrote about in her letters regarding gender bias that she had trouble receiving equal pay for her work as a woman.

Vigée Le Brun lived from 1715–1767 and hailed from France, like Gentileschi her father Louis Vigée a talented painter raised her in the skill. Vigée Le Brun had many high profile clients in the French aristocracy but her main patron was Queen Marie Antoinette who helped her gain membership to the Royal Academy. She married man who was both a painter and art dealer, during her life she traveled Europe however her regional movement was more due the controversies of the French revolution. She had been close to the aristocracy as well as the Queen, when the monarchy was overthrown Vigée Le Brun was listed as exiled from France. She was able to return years later, during her exile with her resilience she continued her work as a painter.

The three self-portraits were selected due to the exceptional efforts of these female painters to challenge the status quo of their time as each excelled in skill gaining great renown. Their self portraits provide insight into their personalities, their values, their measures of success, their skills, and their

creative self-expressions. They have shared a part of themselves through their respective works of art and communicated to those willing to participate on the receiving end of their messages. Their work invites us to evaluate it, consider their messages, delight in the art of it and explore their stories. Their legacy has

stretched far past social roles, regions, and their experience with society’s past limitations meeting us in our present.

creative self-expressions. They have shared a part of themselves through their respective works of art and communicated to those willing to participate on the receiving end of their messages. Their work invites us to evaluate it, consider their messages, delight in the art of it and explore their stories. Their legacy has

stretched far past social roles, regions, and their experience with society’s past limitations meeting us in our present.

It is the hope of this exhibit is to provide further exposure of these female painters for this current and to future generations. We would like to add to the public knowledge of the skills, quality, and respective histories of these women. Their livelihoods depended on their works of art in times where their efforts were breaking barriers. These were bold moves for gender equality, their willingness to put themselves out there, undeterred by social limitation added momentum for breaking gender barriers that bare impact on us today. They are voices meant to be heard, our exhibit is their platform, we are allowing the past to encourage us to be bold, brave, confident, pushing past unhealthy social limitations and honor our freedom to find our own ways of self-expression.